The golden age of Islam The Abbasid caliphs established the city of Baghdad in 762 CE. It became a center of learning and the hub of w...

The golden age of Islam

The

Abbasid caliphs established the city of Baghdad in 762 CE. It became a center

of learning and the hub of what is known as the Golden Age of Islam.

Overview

·

After the death of Muhammad,

Arab leaders were called caliphs.

·

Caliphs built and established

Baghdad as the hub of the Abbasid Caliphate.

·

Baghdad was centrally located

between Europe and Asia and was an important area for trade and exchanges of

ideas.

·

Scholars living in Baghdad

translated Greek texts and made scientific discoveries—which is why this era,

from the seventh to thirteenth centuries CE, is named the Golden Age of Islam.

A

love of knowledge was evident in Baghdad, established in 762 CE

as the capital city of the Abbasid Caliphate in modern-day Iraq. Scholars,

philosophers, doctors, and other thinkers all gathered in this center of trade

and cultural development.. Academics—many of them fluent in Greek and

Arabic—exchanged ideas and translated Greek texts into Arabic.

Chief

Muslim leaders after Muhammad’s death were referred to as Caliphs.The era of

the Abbasid Caliphs’ construction and rule of Baghdad is known as the Golden Age of Islam. It was an era when

scholarship thrived.

Abbasid Caliphate

After the death of Muhammad

and a relatively brief period of rule by the Rashidun Caliphs, the Umayyad Dynasty gained the reins of power.

Based in Damascus, Syria, the Umayyad Caliphate faced internal pressures and

resistance, partly because they displayed an obvious preference for Arab

Muslims, excluding non-Arab Muslims like Persians. Taking advantage of

this

weakness, Sunni Arab Abu al-Abbas mounted a revolution in 750 CE. With support

from his followers, he destroyed the Umayyad troops in a massive battle and

formed the Abbasid Dynasty in its place.

Baghdad

|

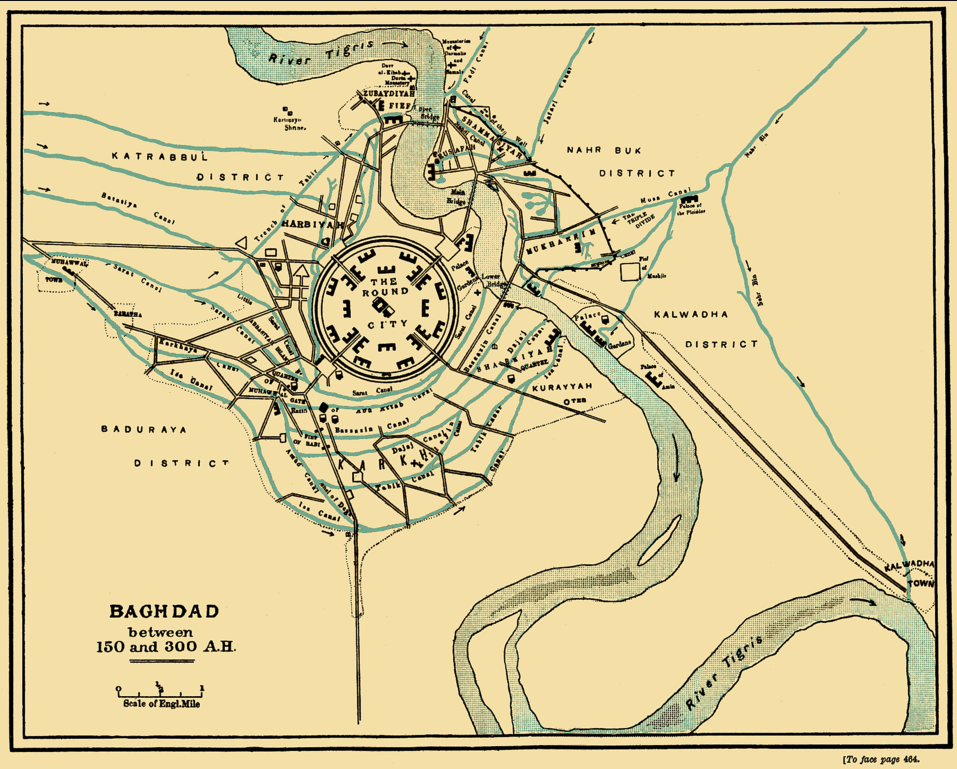

| A map of the city of Baghdad. Image credit: Wikimedia |

The

leaders of the Abbasid Dynasty built Baghdad, the capital of

modern-day Iraq. Baghdad would come to replace and overshadow Damascus as the

capital city of the empire. It was located near both the Tigris and Euphrates

rivers, making it an ideal spot for food production that could sustain a large

population.

The

Abbasids built Baghdad from scratch while maintaining the network of roads and

trade routes the Persians had established before the Umayyad Dynasty took over.

Baghdad was strategically located between Asia and Europe, which made it a

prime spot on overland trade routes between the two continents. Some of the

goods being traded through Baghdad were ivory, soap, honey, and diamonds.

People in Baghdad made and exported silk, glass, tiles, and paper. The central

location and lively trade culture of the city made a lively exchange of ideas

possible as well.

|

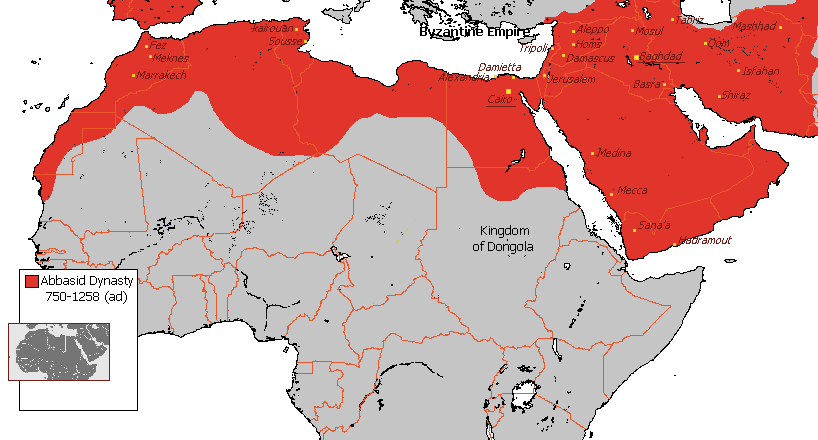

| A map of the extent of the Abbasid Dynasty from 750 to 1258. Image credit: Wikimedia |

Baghdad

attracted many people, including scholars, to live within its borders. To get a

sense of what living in the newly constructed city was like, here’s an excerpt

from the writings of Arab historian and biographer, Yakut al-Hamawi, describing

Baghdad in the tenth century:

The

city of Baghdad formed two vast semi-circles on the right and left banks of the

Tigris, twelve miles in diameter. The numerous suburbs, covered with parks,

gardens, villas, and beautiful promenades, and plentifully supplied with rich

bazaars, and finely built mosques and baths, stretched for a considerable

distance on both sides of the river. In the days of its prosperity the

population of Baghdad and its suburbs amounted to over two [million]! The

palace of the Caliph stood in the midst of a vast park several hours in

circumference, which beside a menagerie and aviary comprised an enclosure for

wild animals reserved for the chase. The palace grounds were laid out with

gardens and adorned with exquisite taste with plants, flowers, and trees,

reservoirs and fountains, surrounded by sculpted figures. On this side of the

river stood the palaces of the great nobles. Immense streets, none less than

forty cubits wide, traversed the city from one end to the other, dividing it

into blocks or quarters, each under the control of an overseer or supervisor,

who looked after the cleanliness, sanitation and the comfort of the

inhabitants.

Tenth-century

historian Yakut al-Hamawi, from Lost History 60-61

Pursuit of knowledge

|

| Scholars at an Abbasid library. Image credit: Wikimedia |

Abbasid

Caliphs Harun al-Rashid and his son, al-Ma’mun, who followed him, established a House of Wisdom in Baghdad—a

dedicated space for scholarship. The House of Wisdom increased in use and

prestige under al-Ma’mun’s rule, from 813 to 833. He made a special effort to

recruit famous scholars to come to the House of Wisdom. Muslims, Christians,

and Jews all collaborated and worked peacefully there.

The Translation Movement

Caliphs

like al-Rashid and al-Ma’mun directly encouraged a translation movement, a formal translation of

scholarly works from Greek into Arabic. The Abbasid rulers wanted to make Greek

texts, such as Aristotle’s works, available to the Arab world. Their goal was

to translate as many of these famous works as possible in order to have a

comprehensive library of knowledge and to preserve the philosophies and

scholarship of Greece. The Abbasids aimed to have philosophy, science, and

medicine texts translated. In addition to Arab Muslim scholars, Syrian

Christians translated Syriac texts into Arabic as well.

Why

were the Abbasids so interested in a massive translation undertaking? In

addition to their desire to have a comprehensive library of knowledge and the Qur’an’s emphasis on learning as a holy activity, they

also had a practical thirst for medical knowledge. The dynasty was facing a

demand for skilled doctors—so having as much knowledge as possible for them to

access was a must.

One

way the Abbasid dynasty was able to spread written knowledge so quickly was

their improvements on printing technology they had obtained from the Chinese;

some historians believe this technology was taken after the Battle of Talas

between the Abbasid Caliphate and the Tang Dynasty in 751. The Chinese had

guarded paper making as a secret, but when the Tang lost the battle, the

Abbasids captured knowledgeable paper makers as prisoners of war, forcing them

to reproduce their craft.

In

China, papermaking was a practice reserved for elites, but the Arabs learned

how to produce texts on a larger scale, establishing paper mills which made

books more accessible. In turn, Europeans eventually learned these papermaking

and producing skills from Arabs.

|

| Bust of Aristotle. Image credit: Wikimedia |

Abbasid advances

During

the Golden Age of Islam, Arab and Persian scholars—as well as scholars from

other countries—were able to build on the information they translated from the

Greeks and others during the Abbasid Dynasty and forge new advances in their

fields. Ibn al-Haythm invented the first camera and was able to form an

explanation of how the eye sees. Doctor and philosopher Avicenna wrote the Canon of Medicine, which helped physicians diagnose

dangerous diseases such as cancer. And Al-Khwarizmi, a Persian mathematician,

invented algebra, a word which itself has Arabic roots.

|

| Portrait of Al-Khwarizmi. Image credit: Wikimedia |

Summary

Scholars living in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate contributed to the preservation of Greek and other existing knowledge about philosophy, astronomy, medicine, and many other disciplines. In addition to preserving information, these scholars contributed new insights in their fields and ultimately passed their discoveries along to Europe.

Bentley, Jerry. H. Traditions and Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. New York: McGraw Hill, 2006, 296-298.

“Battle of Talas,” Wikipedia.

Hamilton Morgan, Michael. Lost History: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Scientists, Thinkers, and Artists. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2007, 60-61

Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab Peoples. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991, 76.

No comments